National Debt/Debt Limit: What You Need To Know

Every few years, Republicans and Democrats battle over increasing the national debt limit. Each side tries to avoid blame for the size of the debt and the need to increase it. They also make dire predictions about what will happen if the debt is not raised (a situation known as default), and debate whether an increase should be accompanied by spending cuts, tax increases, or other policy changes. For Americans, this spectacle raises important questions. Why do we have a national debt – and what can we do about it? What happens if the United States defaults on its national debt?

What Is The National Debt? What Is The Debt Limit?

The national debt consists of bonds (IOUs) issued by the national government of the United States to cover its annual budget deficits. These bonds are sold to private investors, businesses, and other governments. The debt limit is a measure imposed by Congress that caps the size of the national debt. The current national debt is about $31.4 trillion. The debt ceiling was last raised in December 2021.

A common misunderstanding is that the debt limit is raised to enable new government spending. Actually, the debt limit is raised to pay for things the government is already committed to doing. For example, if Congress approves a budget for 2023 that spends $3.3 trillion dollars on government programs but only collects $2.1 trillion dollars in tax revenue, the difference between spending and revenue ($1.2 trillion dollars) is the budget deficit. This deficit must be paid for by increasing the national debt, otherwise the government will not be able to spend money as Congress directed in the budget.

On January 19th, 2023, the current national debt ceiling ($31.3 trillion) was reached. To avoid defaulting on loan payments and spending commitments, the Treasury is taking so-called “extraordinary measures,” which are steps that allow a small amount of additional borrowing. However, without action by Congress to raise the debt limit, the Treasury will soon be unable to pay all the government’s obligations, leading to a default.

How Large Is The National Debt?

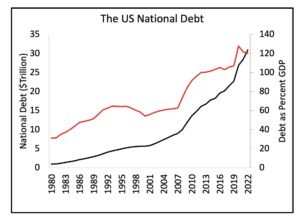

The figure below shows the trajectory of the national debt of the United States from 1967 to 2022. The black line and the left-hand axis maps the total debt, which increased from $330 billion in 1967 to just over $31 trillion in Spring 2023. The red line and the right-hand axis shows the debt as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) or the value of all goods and services produced each year. (Comparing debt to GDP adjusts for changes in the size of the economy, which is a good measure of a nation’s ability to pay off its debt.) Even using this measure, the national debt has increased substantially over time.

Why is the national debt increasing? In part, the increases are the result of emergency spending after economic crises such as the 2008 Mortgage Crisis and the 2020 COVID Pandemic, international conflicts such as the wars in Iraq (2002 – 2012) and Afghanistan (2002 – 2021), and tax cuts on individuals and corporations. However, the main reason for the debt limit increase in recent years is that the federal government has consistently run a budget deficit since the early 2000s, which is a result of government spending outpacing income.

The next figure contrasts the United State’s debt-to-GDP ratio with the other countries in the G7 (a group of the world’s largest industrialized democracies – Canada, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, and Japan). The line for the US is black, Japan is red, and the other G7 countries are in gray. By this measure, the size of the US national debt is marginally higher than that of most other G7 countries (Japan is the exception, with a much higher percentage).

What Are The Consequences of a Large National Debt?

A large national debt can create two primary problems. One is that a significant portion of government revenue must be used to pay interest on existing debt. As these payments increase, there is less and less money available to pay for other programs, from defense spending to Social Security. As a result, it might become impossible for the government to spend additional money to address emerging national needs, such as providing health care to retirees through Medicare.

The figure below shows the percentage of the federal budget consumed by interest payments during 1980 – 2022. As the figure shows, interest payments can decline even as the debt increases. While America’s national debt has increased significantly since the 1980s, interest rates are much lower now compared to then, meaning that the percentage of government revenue needed to pay for the national debt is lower now than compared to years in which interest rates were higher. However, if interest rates increase in the future, interest payments for a rising national debt will require a higher percentage of the federal budget, which reduces the government’s ability to fund programs.

A large national debt can also reduce economic growth. If the debt grows large enough, it can draw off a large portion of the capital available in the economy to invest in new technologies or build new factories. Further, the government might need to increase the interest paid on the debt in order to get people to buy the bonds needed to finance annual deficits. Both effects can decrease economic growth, increase unemployment, and make everyone worse off.

How Is the Debt Limit Increased?

Raising the debt limit requires a congressional resolution enacted by a majority in the House and Senate and signed by the President or, if the President vetoes the resolution, by a 2/3rds majority of the House and Senate. The limit has been raised multiple times in the last several decades. The table below shows the first and last debt limit resolutions enacted during the last four presidencies. Increases have been enacted by both Republican and Democratic Presidents and by both Republican- and Democratic-controlled Congresses. Thus, it is not accurate to say that the national debt is a Democratic or a Republican problem or blame it on a particular President. Elected officials from both political parties have voted for budgets that have deficits and for increases in the debt limit to fund these deficits.

What Happens If the Debt Limit Is Not Raised?

Once extraordinary measures are exhausted, hitting the debt limit means that the federal government cannot issue any additional bonds. At that point, the government would not have enough money to pay for programs approved by Congress and cover interest payments on the existing national debt, a situation known as a default. What happens after a default is unclear – the debt limit has always been increased before this limit was reached.

One possibility is that the Treasury Department would put all government payments on hold, effectively shutting the government down. A shutdown would also affect private companies that have contracts with the government. Depending on the duration of the shutdown, these companies may have to lay off employees to balance the loss of revenue. Default would also stop payments to beneficiaries of government programs, including Social Security, Medicare, and student loans.

Another option is for Congress to either raise taxes, drastically cut government spending, or a combination of both, so that there is a budget surplus and no debt limit increases are needed. As we discuss in another policy brief on the budget deficit, these changes would require large tax increases or very large spending cuts, particularly if popular-but-expensive programs such as Social Security and Medicare are exempted from cuts.

Some politicians have also argued that the Department of the Treasury could act even if Congress did not, and prioritize certain payments such as interest on the debt, national defense, Social Security, and Medicare, and cut spending on other federal programs so that the debt limit was not broken. However, Treasury officials have stated that they do not have the ability or the authority to prioritize payments. Under current law, the Treasury must fund programs exactly in line with the budgets that Congress has enacted – they can’t pick and choose which programs to pay for.

Many economists believe that a default would cause significant damage to the economy. Most obviously, default would suspend about one-tenth of US economic activity that is directly tied to the federal government. A government default would probably cause downgrades of the credit rating of the US government and increase the interest rate the government would pay to borrow money. Default would also suspend payments to businesses that contract with the government as well as vulnerable individuals such as recipients of Social Security, Medicare, unemployment insurance, and student loans. All of these developments, as well as higher interest rates, could put the United States into a severe economic recession and cause a global financial crisis.

In the end, the national debt is not a problem in and of itself – rather, it is a sign that US politicians cannot agree on how to balance taxes and spending. The national debt will stabilize and start to fall only after agreement is reached on how to reduce the government’s annual budget deficits.

Further Reading

Gravelle, Jane G., & Marples, Donald J. (2022). “Addressing the Long-Run Deficit: A Comparison of Approaches.” Congressional Research Service. https://tinyurl.com/mr48b22u.

Chen, S., & Desiderio, S. (2018). “Long-Run Consequences of Debt.” Journal of Economic Interaction and Coordination, 13(2), 365–383. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48647247

Ferguson, R. W., Jr. (2021, September 28). What’s at stake in the debt ceiling showdown. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/whats-stake-debt-ceiling-showdown

Sources

What Is The National Debt? What Is The Debt Limit?

Burman, L., & Gale, W. G. (2023, January 19). 7 things to know about the debt limit. Brookings. https://tinyurl.com/46bh2995.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2022, March 28). America’s Fiscal Future – Federal Debt. America’s Fiscal Future – Federal Debt | U.S. GAO. March 24, 2023, https://tinyurl.com/ynzmnmnh.

“Federal Debt & Debt Management.” U.S. Government Accountability Office. https://www.gao.gov/federal-debt.

(Chart Data) “Debt to the Penny.” U.S. Treasury. https://tinyurl.com/dm7zdpa4.

Department of the Treasury (2023). What Is the National Debt? U.S. Treasury. https://tinyurl.com/ua9uu82y.

Department of the Treasury (2023). Debt Limit. U.S. Department of the Treasury. https://tinyurl.com/devr3j7w.

Martinez, F. Roch, F. Roldan and J. Zettelmeyer (2022). Sovereign Debt. Imf.org. https://tinyurl.com/4379unm6.

How large is the national debt?

Federal debt: Total public debt as percent of gross domestic product. (2022, December 22). St Louis Federal Bank. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GFDEGDQ188S

Department of the Treasury (n.d.). Historical debt outstanding. Retrieved February 23, 2023, from https://tinyurl.com/4ay954u9.

Central Government Debt (As of December 31, 2022). (2023, January 31). Ministry of Finance. https://tinyurl.com/mv8jj9cy.

Cooper, S. (2022, May 19). China’s national debt clock: What’s the current figure (and what’s included)? Commodity.com. https://commodity.com/data/china/debt-clock/

General Government Debt (2022). International Monetary Fund. https://tinyurl.com/yufasjvf.

What Are The Consequences of a Large National Debt?

Chen, S., & Desiderio, S. (2018). “Long-Run Consequences of Debt”. Journal of Economic Interaction and Coordination, 13(2), 365–383. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48647247

Driessen, G., & Marples, D. (2022, December 8). “Debt and Deficits: Spending, Revenue, and Economic Growth.” Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11037

DeSilver, D. (2023, February 14). 5 Facts about the U.S. National Debt. Pew Research Center. March 24, 2023, https://tinyurl.com/43anj89x.

How Is the Debt Limit Increased?

Saturno, James V. (2023). “Introduction to the Federal Budget Process.” Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46240

Wallner, J. (2023). How lawmakers can increase the debt limit. Legislative Procedure. https://tinyurl.com/3kfda2ut.

What Happens If the Debt Limit Is Not Raised?

Debt Limit. (2023). U.S. Department of the Treasury. https://tinyurl.com/devr3j7w.

Bilmes, L. (2023). I helped balance the federal budget in the 1990s – here’s just how hard it will be for the GOP to achieve that same rare feat. https://tinyurl.com/2twbp7pz.

Ferguson, R. W., Jr. (2021, September 28). What’s at stake in the debt ceiling showdown. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/whats-stake-debt-ceiling-showdown

Ams, J., Baqir, R., Gelpern, A., & Trebesch, C. (2019). Sovereign Default. In Sovereign Debt: A Guide for Economists and Practitioners. https://tinyurl.com/36hdybn8

This policy brief was research and written in February – March 2023 by Policy vs. Politics interns Reagan Gautam, Nicholas Markiewicz, and Eli Oaks, and revised by Dr. William Bianco, Research Director for Policy vs. Politics.