Suppose you are reading this brief on an iPad. Apple is an American company, so your tablet must have been produced in the United States. Maybe not. Today, many corporations are headquartered in one country but manufacture in others and buy supplies from many more. This practice is called offshoring. Offshoring allows companies to lower their costs. However, offshoring also moves jobs from the United States to other countries. Is offshoring a good thing or a bad thing for Americans?

What is offshoring?

Companies offshore their operations when they move some or all business operations abroad, typically from a high-cost country to a country with lower costs. Because countries have different labor and trade laws and standards, some portions of a corporation’s operations, like research and development, low-skilled assembly jobs, or customer service phone centers, for example, can be performed at a lower cost in other countries. Offshoring allows corporations to reduce their costs, lowering prices and increasing profits.

What’s the difference between offshoring and outsourcing?

A company outsources part of its operations when it contracts with a different company to provide a service or produce a product rather than performing that work with company employees. An example of outsourcing is when a company hires an accounting firm to manage financial operations instead of having an accounting department. On the other hand, offshoring refers to operations that cross country borders. For example, a company can offshore by moving its manufacturing operations to another country, or contract with a company in another country to build products.

Offshoring, particularly of manufacturing and low-skilled jobs, like factory-based assembly jobs, began on a large scale in the 1970s and 1980s. Offshoring of higher-skilled jobs such as accounting or research and development became more popular in the early 2000s.

Who engages in offshoring? Why do they offshore?

Many companies utilize offshoring, particularly in IT, manufacturing, and customer service. For example, car manufacturers frequently operate assembly plants or supply parts plants in other countries to reduce the labor cost of car manufacturing. Similarly, many companies operate customer service call centers in other countries because wages are lower overseas than in the U.S.

Some companies use offshoring to avoid U.S. corporate taxes by opening subsidiary companies in countries with lower corporate tax rates. According to one study, in 2016, over 73% of the Fortune 500 (the 500 largest corporations in the U.S.) had offshore subsidiaries in these ‘tax haven’ countries.

Leaving tax benefits aside, the primary motivation for offshoring is to reduce labor costs, usually by substituting cheaper foreign workers for employees in the U.S. This shift in manufacturing jobs occurred in the 1990s and early 2000s. One study found that over 40 percent of the decline in U.S. manufacturing jobs between 1993 and 2011 was due to offshoring. However, a second analysis found that in many firms, total employment did not decrease due to offshoring – the reduction in manufacturing jobs was offset by hiring in sales, management, and other areas. Additionally, average wages in offshoring firms did not decrease as manufacturing jobs were moved to other countries.

How much of the U.S. economy is based on offshoring?

It is hard to say. Many firms purchase at least some goods or services from sellers outside the U.S. A smaller percentage have located manufacturing, research, or distribution facilities outside the country.

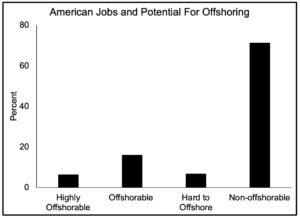

What is clear is that most jobs that can be offshored have already been moved. One well-cited 2009 study by the economist Alan Binder argued that as a percentage of total employment, the number of easily offshored jobs is relatively low. Binder divided jobs into four categories (examples in parenthesis):

- Highly offshorable (Computer programmers and systems analysts, telemarketers, bookkeeping, accounting)

- Offshorable (Computer software engineers, accountants, machine operators, team assemblers and production worker helpers, bill collectors)

- Hard to offshore (Operations managers, stock clerks, shipping and receiving)

- Non-offshorable: (Health and safety engineers, music directors, photographers)

The figure below shows the percentage of total jobs in America in each category.

Source: Levine (2012)

Binder’s analysis suggests that relatively few jobs in America (less than 10 percent) are vulnerable to offshoring. For the rest, offshoring adds new complexities or does not save money.

If only a few people lose jobs because of offshoring, why is it so controversial?

Offshoring has always been controversial. A 2013 study found that 95% of U.S. respondents did not approve of it, mainly because it would result in the loss of jobs within the United States. These opinions likely reflect the move of manufacturing jobs to other countries.

While the data on offshoring suggests that not many jobs have been lost overall, these losses have been concentrated in certain industries such as manufacturing (especially autos). For workers in these industries, the costs of offshoring are immediate and large, and it is no surprise they are unhappy with the process.

A second concern about offshoring is whether the process will continue so that many other industries will offshore large numbers of jobs. However, a study by Mukherjee and others found that the increase in offshoring has decreased over the last decade. The authors argued that most easily offshored jobs have already been moved to other countries. As a result, past increases in offshoring are unlikely to be repeated.

Further Reading

Boleter, Kathleen, and Jim Robey. (2020). Strategic Reshoring: A Strategic Perspective, https://tinyurl.com/3z8dvhba, accessed 4/24/24.

Tate, W.L. & Bals, L. (2017). “Outsourcing/offshoring insights: going beyond reshoring to rightshoring,” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 47(2), pp. 106-113. http://tinyurl.com/54ymaaac, accessed 12/14/23.

Levine, L. (2012). Offshoring (or Offshore Outsourcing) and Job Loss Among U.S. Workers. Congressional Research Service. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL32292.pdf, accessed 12/14/23.

Sources

What is offshoring?

Tate, W.L. & Bals, L. (2017). “Outsourcing/offshoring insights: going beyond reshoring to rightshoring,” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 47(2), pp. 106-113. http://tinyurl.com/54ymaaac, accessed 12/14/23.

Levine, L. (2012). Offshoring (or Offshore Outsourcing) and Job Loss Among U.S. Workers. Congressional Research Service. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL32292.pdf, accessed 12/14/23.

What’s the difference between offshoring and outsourcing?

Levine, L. (2012). Offshoring (or Offshore Outsourcing) and Job Loss Among U.S. Workers. Congressional Research Service. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL32292.pdf, accessed 12/14/23.

Who engages in offshoring? Why do they offshore?

Philips, Richard, Mat Gardner, Alexandria Robins, and Michelle Surka. (2017). Offshore Shell Games, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and U.S. PIRG Education Fund, https://tinyurl.com/42rt8u49, accessed 4/24/24.

Farrell, D. (2005). Offshoring: Value creation through economic change. Journal of Management Studies, 42(3), 675-683. http://tinyurl.com/5y9cpwuu, accessed 12/14/23.

Bramucci, A., Cirillo, V., Evangelista, R., & Guarascio, D. (2021). Offshoring, industry heterogeneity and employment. Structural change and economic dynamics, 56, 400-411.

How much of the US economy is based on offshoring?

Levine, L. (2012). Offshoring (or Offshore Outsourcing) and Job Loss Among U.S. Workers. Congressional Research Service. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL32292.pdf, accessed 12/14/23 (Chart Data).

Blinder, A. S. (2009). How many US jobs might be offshorable? World Economics, 10(2), 41.

Cardoso, M., Neves, P. C., Afonso, O., & Sochirca, E. (2021). The effects of offshoring on wages: a meta-analysis. Review of World Economics, 157, 149-179.

Boehm, C. E., Flaaen, A., & Pandalai-Nayar, N. (2020). Multinationals, offshoring, and the decline of US manufacturing. Journal of International Economics, 127, 103391.

If only a few people lose jobs because of offshoring, why is it so controversial?

Mansfield, E. D. & Mutz, D. C. (2013). Us Versus Them: Mass Attitudes toward Offshore Outsourcing. World Politics, 65(4), 571–608. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42002224, accessed 12/14/23.

Levine, L. (2012). Offshoring (or Offshore Outsourcing) and Job Loss Among U.S. Workers. Congressional Research Service. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL32292.pdf, accessed 12/14/23.

Mukherjee, D., Kumar, S., Pandey, N., & Lahiri, S. (2023). Is offshoring dead? A multidisciplinary review and future directions. Journal of International Management, 29(3), 101017.

Contributors

Julia Acevedo (Intern) is a Political Science and Public Policy double major at Susquehanna University and is expected to graduate in May 2024 and pursue a Masters degree in Public Health.

Elijah Oaks (Intern) is a student at Dartmouth College. He is expected to graduate in May 2024 with a major in English and a minor in Religion. He is a Policy Fellow at The Cicero Institute.

Dr. Laura Bucci (Subject Matter Expert) is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Saint Joseph’s University. Her research focuses on how labor decline/resurgence influences political behavior, public policy, and state politics. She received her PhD from Indiana University.

Dr. Robert Holahan (Content Lead) is Associate Professor of Political Science and Faculty-in-Residence of the Dickinson Research Team (DiRT) at Binghamton University (SUNY). He holds a PhD in Political Science in 2013 from Indiana University, where his advisor was Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom.

Dr. William Bianco (Research Director) received his PhD in Political Science from the University of Rochester. He is Professor of Political Science and Director of the Indiana Political Analytics Workshop at Indiana University. His current research is on representation, political identities, and the politics of scientific research.

Publication Log

Published 6/18/24