In the past two decades, U.S. natural gas and oil production has increased to the point that America is now a net exporter of these commodities. This change is due to a new technology, hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. How does fracking fit into the debate over climate change?

What Is Fracking?

Fracking is a technique for accessing oil and natural gas from underground shale formations and existing wells where production has declined. A combination of water, sand, and chemicals are injected below ground to create fractures in the rock, allowing the oil and gas to move into a well for extraction. Fracking is incredibly effective at extracting oil and gas from areas that had previously been considered unreachable. It has contributed to dramatically expanding oil and gas production in the United States.

How Much Energy Is Produced By Fracking?

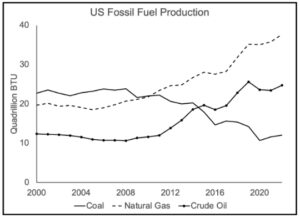

Oil and gas production in the United States had been declining from the 1970s to the early 2000s as all the more easily accessible reserves were increasingly depleted. The advent of fracking reversed this trend: the United States became the world’s largest natural gas producer in 2009 and oil in 2014.

Source: EIA (2024a)

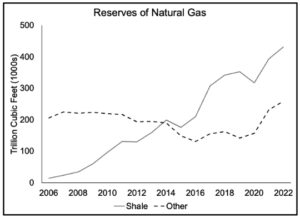

Overall, data from the US Energy Information Agency shows that increased fracking drove this change: production from shale formations – those for which fracking was developed – comprises 75% of U.S. natural gas production and 48% of oil production. And, as the second chart shows, fracking has led to a substantial increase in proven natural gas reserves in the U.S..

Source: EIA (2024b)

What are the disadvantages of fracking?

While fracking has generated a massive boom in domestic oil and gas production, it has environmental costs. One issue is that fracking uses a substantial amount of water and can exacerbate shortages in areas where demand exceeds what can be supplied by local aquifers.

Fracking also generates waste from drilling muds, flowback, and the produced “brines” that must be properly treated and disposed of. Whether due to equipment malfunction, human error, or improper storage practices, it is estimated that about 2% of wells dump these byproducts into streams and roads, damaging the ecosystem and contaminating drinking water with toxic and carcinogenic compounds.

Fracking has also been linked to increased earthquakes in the Central and Eastern United States. Before fracking, there were about 25 earthquakes per year in this region. Once fracking began in 2009, there have been at least 58 earthquakes per year. It’s important to emphasize that to date many of these earthquakes have a magnitude between 3 and 4, strong enough to be felt but not enough to cause damage.

Lastly, while greenhouse gas emissions from natural gas production are far lower than coal, natural gas wells may leak methane through loose joints and valves or from open wastewater evaporation ponds.

What would happen to energy production if we stopped fracking?

A ban on fracking would move the United States from being a net exporter of natural gas to an importer, as natural gas consumption far exceeds the production from conventional techniques. Similarly, ending fracking would reduce U.S. production of oil by almost 40%. These changes would cause a spike in both oil and natural gas prices, affecting families and businesses.

Beyond these challenges, an end to fracking would also present new geopolitical complications. By way of example, Russia is the world’s largest exporter of natural gas. If the U.S. were to depend on Russian exports, it would make it far more difficult for policymakers to check Russian aggression in Ukraine.

Lastly, while fracking can negatively impact the environment, the increased natural gas production has reduced coal consumption by power plants and other energy producers. If natural gas became prohibitively expensive, a portion of energy production would likely return to coal, which has been found to be far worse for the environment.

How does fracking fit into the debate over climate change?

At one level, increased production of fossil fuels by fracking is a source of climate change, as energy production using natural gas and oil releases greenhouse gas CO2 into the atmosphere, likely contributing to increased global temperatures. However, increased production of natural gas and oil has led to reductions in the amount of coal burned to generate electricity. In this way, energy production through fracking is a low-cost way to reduce overall CO2 emissions in the short run and buy time to develop renewable energy technologies.

Further Reading

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2024). Monthly Energy Review, “Primary energy production by source.” http://tinyurl.com/5n924py9, accessed 4/11/24.

Jackson, R. B., Vengosh, A., Carey, J. W., Davies, R. J., Darrah, T. H., O’Sullivan, F., & Pétron, G. (2014). The Environmental Costs and Benefits of Fracking. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 39, 327-362. https://tinyurl.com/3nada88x, accessed 4/11/24.

Diaz, M. N. (2021). U.S. Energy in the 21st Century: A Primer. Congressional Research Service. https://tinyurl.com/3p5cn5hk, accessed 4/11/24.

Sources

What Is Fracking?

Jackson, R. B., Vengosh, A., Carey, J. W., Davies, R. J., Darrah, T. H., O’Sullivan, F., & Pétron, G. (2014). The Environmental Costs and Benefits of Fracking. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 39, 327-362. https://tinyurl.com/3nada88x, accessed 4/11/24.

Norris, J.Q. et al. (2016). Fracking in Tight Shales: What Is It, What Does it Accomplish, and What Are Its Consequences? Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 44, 321-51. https://tinyurl.com/27rr6s4k, accessed 4/11/24.

How Much Energy Is Produced By Fracking?

Diaz, M. N. (2021). U.S. Energy in the 21st Century: A Primer. Congressional Research Service. https://tinyurl.com/3p5cn5hk, accessed 4/11/24.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2024a). Monthly Energy Review, “Primary energy production by source.” http://tinyurl.com/5n924py9, accessed 4/11/24. (Chart Data).

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2024b). U.S. Crude Oil and Natural Gas Proved Reserves, Year-end 2022. https://www.eia.gov/naturalgas/crudeoilreserves/, accessed 4/11/24. (Chart Data).

What Are The Disadvantages of Fracking?

Gleeson T., Wada, Y., Bierkens, F. P. M., & van Beek, P. H. L. (2012). Water balance of global aquifers revealed by groundwater footprint. Nature, 488, 197-200. https://tinyurl.com/mpn27asr, accessed 4/11/24.

Jackson, R. B., Vengosh, A., Carey, J. W., Davies, R. J., Darrah, T. H., O’Sullivan, F., & Pétron, G. (2014). The Environmental Costs and Benefits of Fracking. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 39, 327-362. https://tinyurl.com/3nada88x, accessed 4/11/24.

McGarr, A., Bekins, B., Burkardt, N., Dewey J., Earle, P., Ellsworth W., Ge, S., Hickman, S., Holland, A., Majer, E., Rubinstein, J., & Sheehan, A. (2015). Coping with Earthquakes Induced by Fluid Injection. Science, 347(6224), 830-831. https://tinyurl.com/ehnbwz75, accessed 4/11/24.

Osborn, S. G., Vengosh, A., Warner, N. R., & Jackson, R. B. (2011). Methane contamination of drinking water accompanying gas-well drilling and hydraulic fracturing. Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences, 108(20), 8172-8176. https://tinyurl.com/mscy58mx, accessed 4/11/24.

Bonetti, P., Leuz, C., & Michelon, G. (2023). Internalizing Externalities: Disclosure Regulation for Hydraulic Fracturing, Drilling Activity and Water Quality. National Bureau of Economic Research, 30842. https://tinyurl.com/382cfpza, accessed 4/11/24.

Haley, M., McCawley, M., Epstein, A. C., Arrington, B., & Bjerke, E. F. (2016). Adequacy of Current State Setbacks for Directional High-Volume Hydraulic Fracturing in the Marcellus, Barnett, and Niobrara Shale Plays. Environmental Health Perspectives, 124(9), 1323-1333. https://tinyurl.com/2xmu25uj, accessed 4/11/24.

What Would Happen To Energy Production If We Stopped Fracking?

Jenner, S., & Lamadrid, A. J. (2013). Shale gas vs. coal: Policy implications from environmental impact comparisons of shale gas, conventional gas, and coal on air, water, and land in the United States. Energy Policy, 53, 442-453. https://tinyurl.com/ey4jpcwp, accessed 4/11/24.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2024). Monthly Energy Review, “Primary energy production by source.” http://tinyurl.com/5n924py9, accessed 4/11/24.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2021). International Energy Outlook 2021. https://tinyurl.com/y5jp8nws, accessed 4/11/24.

Contributors

Schuyler Bordeau (Intern) is a Political Science and Philosophy double major at Wake Forest University expected to graduate in May 2024. Upon graduation, she will join Capstone in Washington, D.C. as a Policy Associate.

Noah Martinez (Intern) is a Political Science major at the University of Illinois Chicago expected to graduate in 2024. In addition to his current role at Policy vs Politics, he is an intern at Joe Moore Strategies LLC, a government relations consulting firm.

Dr. Robert Holahan (Subject Matter Expert) is Associate Professor of Political Science and Faculty-in-Residence of the Dickinson Research Team (DiRT) at Binghamton University (SUNY). He holds a Ph.D in Political Science in 2013 from Indiana University-Bloomington, where his advisor was Elinor Ostrom.

Dr. Nick Clark (Content Lead) is Professor of Political Science at Susquehanna University, where he is also Department Head in Political Science and Director of the Public Policy Program and the Innovation Center. He received his Ph.D. from Indiana University and researches political institutions, European politics, and the politics of economic policy.

Dr. William Bianco (Research Director) received his Ph.D in Political Science from the University of Rochester. He is Professor of Political Science and Director of the Indiana Political Analytics Workshop at Indiana University. His current research is on representation, political identities, and the politics of scientific research.

Publication Log

Published 5/21/24